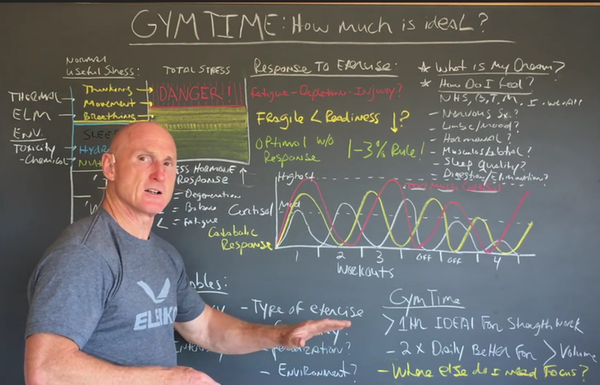

Last week, in part one of this short series on gym time, I talked about how much time you should ideally be spending in the gym, in order to best handle the stress of exercise, and also discusses the yin and yang of cortisol. (If you didn’t get a chance to watch it, start with part one first, before moving to this week’s concluding segment.)

Today, we’ll continue our journey by studying the variables so you’re ready for exercise, getting into the frequency/intensity relationships with cortisol and how our bodies react to them and being very clear about what your dream is for exercise, plus a few other considerations.

Study the variables

Before making any decisions about how hard or how often to train, you must study the variables:

- Frequency

- Duration

- Intensity

- The type of exercise

- Complexity

- Periodization factors

- Environment

For example, if you’re training for a marathon by doing a lot of hill running in the mountains on hot days, you’re adding a lot of thermal stress to your body, but most people don’t take that into account in their weekly exercise diaries.

Usually, the more complex the exercise is, the faster the nervous system fatigues and the higher the risk of injury there is if you keep training past the point you can orchestrate those movements under load and with skill.

If your periodization is wrong, it could be the way you approach your exercise and adjust the variables – reps, sets, loads, tempo and intensity or how many days you do a certain exercise or program a week or month or even micro- or macro cycles.

All of these factors play into the decisions you make that allow you to keep living in that 1-3 percent response rate we discussed in part one, UNLESS you‘re in a specific late-stage training phase when you’re pushing yourself into deeper levels of exhaustion in preparation for competition. Even then, you need to be managed by someone who has a good handle on that or you’re just hurting yourself.

Sometimes, I will push athletes into the yellow zone and close to the red for very short periods of time, but these elite level performers — people like Mike Salemi, my friend and successful kettlebell athlete — are well trained on how to manage all of this stuff.

Cortisol profiles

As you begin to pay closer attention to your workouts, you may start to notice that you’re getting more micro traumas than you expected.

One thing that gets athletes in trouble: Their muscles feel good but they aren’t realizing the accumulation of micro traumas in musculo-tendinous junctions, tendinous insertions and bones. Connective tissues take four to six times longer to heal than muscles due to the lack of direct blood flow to those areas. That’s when you see all sorts of things starting to manifest, like jumper’s knees, rotator cuff problems and low back problems.

In a sport like wrestling where you’re getting your arms and limbs torqued and hurt a lot, you can sustain injuries that could take six weeks to recover even under ideal conditions, yet you don’t even realize it because you may not have enough sensory awareness to recognize it.

If you’re not getting enough rest to normalize your cortisol levels, you won’t be able to come into your next workout safely either.

Let’s say you stay in the gym 90 minutes instead of the suggested 60 minutes and you’re training at a 75 percent of 1RM intensity or higher. Not only do you have a higher response, it takes longer to recover because you have much more tissue destruction in your body.

Plus, if you’re not getting enough sleep, the amount of time your body needs to do repairs keeps getting pushed forward. It’s a lot like distracting your mechanic while he’s working on your car. It may be take him 12 hours to complete a four-hour job if you keep getting in the way!

In other words, it takes longer and longer to recover and you’ll see cortisol levels get higher depending on how you space workouts timewise. If you push it too hard, your cortisol levels can go very high, and it takes even longer to recover.

One final variable to consider is the “monkey see, monkey do” behaviors that are all too common in gyms. Be very careful about mimicking what everyone else is doing in the gym. If your buddy’s training hard all the time and you’re trying to keep up with him, but you know it’s not good for you to do it… that’s childish.

I’ve seen athletes ranging from the fairly low to nearly non-existent levels of readiness to the well prepared all given the same workout by coaches working with elite sports teams. General prescriptions produce general problems which means lots of people get them.

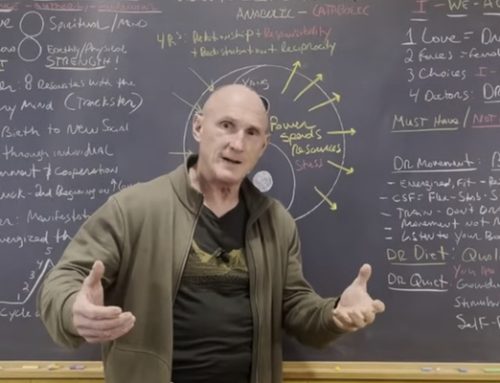

What is your dream?

Another very important thing to consider: Ask yourself why you’re doing this exercise in the first place, based on your dream.

If you don’t know what your dream is, what reasons motivate you to monitor yourself? If you’re not invested in this process, you’re probably going to the gym because it feels good.

But, if you want to keep going to the gym, you have to be careful not to emulate the workouts of athletes you see on TV or read about in magazines. How these elite athletes work out may be way above your level. You can never escape paying attention to yourself and your body.

But, until you know what your dream is, you’ll never figure out how much work is the right amount, what exercises to choose or even if you’re going in the right direction.

Not knowing your dream isn’t an intelligent way to exercise, especially with the boom of functional exercise and too many people jumping right into more explosive, hardcore things they’re very unprepared to do like kettlebell or CrossFit training.

How do I feel?

Also, you have to ask yourself how you feel which means managing the six CHEK Foundation Principles — nutrition, hydration, sleep, breathing, thinking and movement — plus figuring out where your energy is invested and giving yourself enough time at the “I” level.

Are you too invested in the “We” or the “All” level and is it too depleting and interfering with your ability to manage those foundational factors effectively to meet the needs of your dream?

If you’re not taking these things into account, you’ll certainly be heading to the red zone and your longer workouts will probably be very harmful to you.

Either you need to have a clear objective about what your dream really is and know there’s a time limit or look deeply into what kind of mental/emotional issues you haven’t been dealing with. You’re probably avoiding something very important and using exercise as a drug. (We go into these details more deeply in our CHEK Exercise Coach and Holistic Lifestyle Coach programs.)

Again, let me emphasize the 1-3 percent rule we discussed last time. If you can’t improve today’s performance in the gym over your last workout by 1-3 percent, you don’t belong in the gym.

You want to go to the gym with an awareness that exercise can be used therapeutically for almost any condition, even if it means using the zone exercises I describe in How to Eat, Move and Be Healthy! which are highly restorative, yin ones.

Going to the gym may mean times when you’re focusing more on your joint mobilization and stretching to balance your body and paying more attention on areas of your body that aren’t responsive or where you have chronic problems.

That’s often the case when you’ll need to find a CHEK Professional who knows how to assess the entire CHEK Totem Pole to identify things that may be the real cause of your health problems or symptoms you may not realize are coming from higher up in the control systems of your body. You can learn a lot of these self-management techniques in my ebook, The Last 4 Doctors You’ll Ever Need, too.

If you want to learn more about the basics of designing an exercise program, my book Movement That Matters, can teach you a lot of important stuff that’s rarely taught to exercise professionals. And for those of you ready to really learn about program design, I recommend you study my two correspondence courses on the subject: Program Design: Choosing Reps, Sets, Loads, Tempo and Rest Periods and Advanced Program Design.

Be warned that Advanced Program Design is not for the faint-hearted! You will need to have a thorough understanding of all the principles in the first Program Design course, and feel proficient at writing basic exercise programs in order to fully understand the more advanced course.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this short series, and have a better understanding about all of the critical variables that can affect your time at the gym.

There’s a HUGE DIFFERENCE! between doing the right amount of exercise and hurting yourself in the gym. If you pay attention to your body, study the variables I’ve listed here and always keep your eyes on your dream, you’ll never go wrong!

Love and chi,

Paul