Today, I’d like to talk about gym time, specifically how much is enough. There’s a lot of controversy about that subject and, as usual, plenty of research but much of it is conflicting. That’s typical for the scientific community.

My goal for this short series is to help you make more intelligent decisions and get better results about your time in the gym.

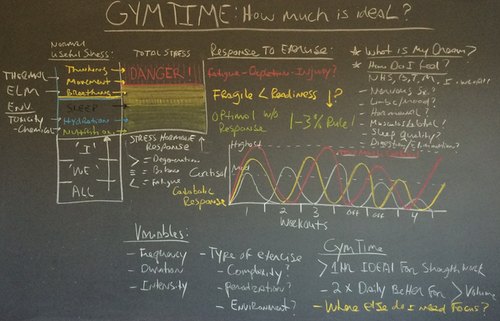

This time, I’ll discuss factors you should be aware of, like stress – how your body handles it – cortisol and the other glucocorticoid hormones, and other important factors involved in calculating how much exercise is ideal for you.

You can review much of this information on total stress accumulation in my book, How to Eat, Move and Be Healthy!. (There’s a whole chapter on stress starting on page 188.)

Today, when I’m talking about how much gym time is enough, I’m specifically focusing on resistance training, not endurance training. It’s not unusual for endurance athletes to workout for 90 minutes or longer, depending on the type of athlete, the event they are training for or the phase of their training.

However, many of the things I’ll share with you about stress management and an awareness of how your body is responding apply to every athlete no matter what sport you’re pursuing. These principles even apply if your “athletic pursuit” is raising young children or being a bricklayer.

No more than an hour

What I’ve found through years of experimenting on myself and others, plus keeping very detailed records, is that you should spend no more than an hour in the gym, including your warmup time.

In some cases, I’ll modify that to say your workout begins when your warmup is finished, but that does depend on how healthy, balanced and ready you are athletically for strenuous activity.

This warmup period includes mobilization of the joints and stretching as needed to balance the body. Sometimes athletes have to spend 35-40 minutes on this because they’re in a restorative phase. Again, this depends on the needs of the individual and their overall stress profile, and is more detailed that I can go into here. If you are interested on this subject, I recommend you study my two correspondence courses on program design: Program Design: Choosing Reps, Sets, Loads, Tempo and Rest Periods and Advanced Program Design.

If you need more time in the gym to accomplish an objective and you want to avoid the negative effects of elevated stress hormones (adrenaline, cortisol or any of the other glucocorticoid family), you’ll find that it’s better to do two shorter workouts in one day.

When I was deep into research on the hormonal profiles of elite Russian Olympic weightlifters many years ago, I found athletes who were training 90 minutes or more a day started having negative responses due to excessive cortisol accumulation.

One thing stood out: There was a greater incidence of injury after about three weeks of training. If athletes didn’t back down and get some rest, they would be in trouble.

I’ve heard world famous strength coach Charles Poliquin say, “If you’re in the gym longer than an hour, you’re not training. You’re making friends.”

Here are some things you need to consider to see whether your time is really productive versus being unproductive and damaging.

If you have a habit of doing too much in the gym yet know you aren’t getting good results, you may need to consider if you have an exercise addiction. I define an addiction as any repeated behavior that doesn’t produce the results you want!

If you tell me no matter how hard you train you can’t put on muscle, you’re always getting hurt or having trouble recovering from injuries, all of these are indicators that you may be medicating yourself with exercise and deeper issues are being avoided that need to be addressed.

Or, as some of my clients do, you pay a lot of money to me or a trainer for good advice, yet you continue to do what you’ve always done!

ALL stress matters

All stresses in the human body-mind accumulate, so there’s no such thing as gym stress that is exclusive to all other kinds of stressors (food, money, relationships) in your life. We’re still pretty Paleolithic in our holistic understanding of exercise, and that’s true even at the most elite levels.

Unfortunately, too many people still hold “no pain-no gain” attitudes, but that’s slowly changing.

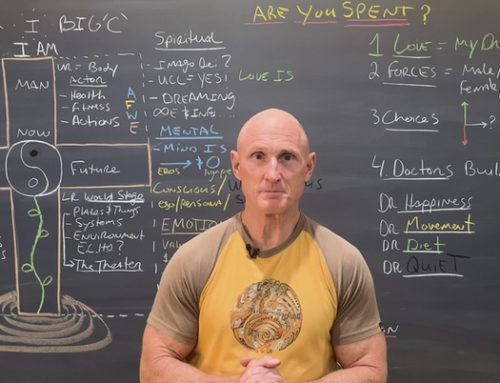

The more stress you accumulate, the worse your response to exercise is. As you see in my chart, in the green area, you have an optimal workout response.

That’s where we apply Olympic coach Charlie Francis’ 1-3 percent rule: If you cannot improve today’s performance in the gym over your last workout by 1-3 percent, you don’t belong in the gym. In fact, you’re working against yourself.

This is particularly important for strength and power athletes or those who use high intensity or high resistance training, especially body builders. When you’re breaking down a lot of muscle and connective tissue, you need a fairly high level of cortisol (a catabolic hormone) to do the cleanup work and lay down new tissue just the way a good painter will sandblast a house to get rid of all of the old paint before putting new paint on.

The yin and yang of cortisol

However, if you have too much cortisol, your tissues will begin to degrade and degenerate. If you’ve ever had physicians injecting things like rotator cuff tendons, patella tendons, knee or backs, research shows that you should never use more than three injections within a given period of time (probably a year) because it increases the risk of tissue damage or breakage.

Also, cortisol is an activating hormone. Its yang function is that it stimulates the reticular activating system and the brain to wake you up and give you a lot of action. Ideally, cortisol levels for most people reach a peak level sometime between the time they get up and about noon.

Of course, the pace and nature of how you “turn yourself on” in the morning will be a little different. Plus, if you have to use coffee, tea or other stimulants to get yourself going in the morning, that’s another indication you’re in trouble and are already suffering from adrenal fatigue and chronically low levels of cortisol.

The yang function of cortisol is that it activates the system. If it’s too high, cortisol has a precursor — adrenaline — that can make you anxious and nervous (give you an ADD kind of mind). Also, it’s harder for you to learn new things because it switches you into a stress reaction profile which gives you left-brain dominance (a reliance on doing what you’ve always done, instead of changing your behavior to something more productive).

The feminine aspect is that it controls and reduces inflammation. However, if your body gets too much cortisol, not only is it tissue-destructive, your liver has to detoxify your own cortisol. If you push any hormone too high, it becomes toxic to the body and another form of stress.

Looking at our daily stressors – the six Foundation Principles I teach in my Holistic Lifestyle Coaching (HLC) program (three yin and three yang) – we use nutrition, hydration and sleep as our main means of bringing in nutrients and accumulating the time and energy we need to restore our bodies.

We breathe to excite the system, and move and think to get things done, although thinking can be more stressful than anything else you can do.

We need a normal or useful amount of stress – eustress – to keep our bodies healthy and grow. If we don’t get stress of the mind, then we don’t develop our mental abilities. If we don’t stress our bodies with movement, we get too weak for the environment in which we live.

If we don’t breathe effectively, our biochemistry gets screwed up and we’re more prone to binge-eat, resort to stimulants and quick energy sources. If we don’t get enough sleep, we can’t recharge and repair our bodies effectively. If we don’t adequately hydrate our bodies, our biochemistry starts to have problems.

Resources

I cover these applications more deeply in How to Eat, Move and Be Healthy! as well as my Last 4 Doctors You’ll Ever Need book, HLC 1 and CHEK Exercise Coach program, our entry level Advanced Training Program for people wanting to master the science and application of exercise.

With all of these factors playing roles in response to our stress hormones, if our stresses are optimal (the green zone), we can train hard.

However, if we experience a more fragile response (the yellow zone), we’re less ready to train and improve by 1-3 percent. If we get into trouble (the red zone), we’re in a state of fatigue and depletion and injury is highly likely.

In part 2, I’ll discuss what happens when we train too frequently, too long and with too much intensity in the gym. Also, I’ll talk about ways you can manipulate that and monitor your body, as well as share tips and resources to support you in optimizing your exercise investment.

Love and chi,

Paul